Heatwave Hell in Maryland

by: Hamani Wilson, Asia Jackson, Zarif Azher, Nasif Azher, Dr. Sacoby Wilson

Heat is the nation’s deadliest weather disaster, killing as many as 1,200 people a year in the United States [1]. According to a 2020 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a total of 10,527 deaths resulting from exposure to heat-related conditions were identified from 2004 to 2018 with approximately 90% of these heat related deaths occurring during the months May — September [2].

Maryland is no exception to this concern. The state is projected to experience an additional 30 days of dangerous heat by 2050 [3], which is especially troubling for the roughly 110,000 residents who are highly vulnerable to excessive heat. In 2019 alone, 21 individuals died from heat-related causes [4], a number which will undoubtedly increase along with occurrences of extreme heat.

Echoing other environmental injustices such as air pollution, according to the CDC, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities are at significantly higher risk of deaths related to heat exposure [2].

The state of Maryland is particularly adversely impacted by climate change and resulting phenomena, including flooding, hurricanes, wildfires, storms, and increasing heat. For example, surrounding sea levels have risen by 10 inches since 1950 [5] and are projected to rise another 2.1 feet by 2050 [6]. Maryland has over 3,000 miles of shoreline and is thus the fourth most vulnerable state to these effects of sea-level rises, stemming from climate change [7]. A similar issue was laid bare when due to extreme rain, Ellicott City, Maryland, experienced a catastrophic once-in-1000-years flood in 2016 — and then again in 2018 [8]. This reflected the 70% rise in precipitation during heavy rain that the Northeast region of the US (where Maryland is located) saw between 1958 and 2012 [9].

Caption: An image showing the catastrophic flooding in Ellicott City, Maryland, in 2018. Extreme weather events like this one are predicted to become increasingly common. SOURCE: The Washington Post

The focus of this report is on excessive urban heat in Maryland, and the impacts it brings. Just as rising sea levels, increased flooding, and wildfires are troubling symptoms of climate change, although it is not as well-documented, excessive heat is too.

Within Maryland, Baltimore is an area of specific focus as it is predicted to be one of the top ten cities that have the most days of excessive heat in the country by 2050 [10]. The communities within the state that are in the most vulnerable position are the frontline and fence line communities that are predominantly inhabited by people of color; Baltimore is a prime example of this, with a population that is roughly 62% African-American [11].

Heat Waves and Climate Change

Heat waves can be defined as periods of time where heat and humidity are relatively elevated for a longer duration than expected. Though they have occurred naturally for billions of years, as consequences of climate change have materialized in recent times, heat waves appear increasingly frequently and with greater intensity.

To illustrate the extent to which climate change is a contributing factor, consider that the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (NOAA) has declared 2020 to have been the hottest summer ever recorded [12]. A recent report conducted by the Maryland Department for Health (MDH) suggests that the occurrence of summertime extreme heat events more than doubled during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s compared to the 1960s and 1970s in Maryland [13]. These issues are not going away; summertime high temperatures in the state are expected to increase 6–7 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050, and the number of heat waves and the duration of heat waves could double by the end of the century [14]. Around the same time, it is projected that the coldest winters in the state will feel like the warmest ones we have now [15]. As we will discuss, intensified by urban heat islands, heat is adversely impacting the health of vulnerable Maryland citizens and will continue to do so.

What is an Urban Heat Island (UHI)?

Urban Heat Islands are typically urbanized areas that experience higher temperatures than outlying areas and surrounding suburbs. Inner city communities absorb and trap more heat than other communities, because they lack greenspaces and trees which cool spaces by releasing moisture, through a process known as evapotranspiration. The greenspaces and trees instead give way to vast amounts of cement and concrete used to develop infrastructure. Think about how parks are often destroyed to build shopping centers or parking lots. Initial studies conducted by the World Meteorological Organization [16] and Oke [17], cited in Gorsevski et al. [18], revealed that the Urban Heat Island effect can increase air temperature in an urban city by between 2 and 8°C and recent studies illustrate that a more accurate range is between 5 and 15°C [19]. Akbari and Rose [20] found that the average urban surface of four different metropolitan areas in the USA were characterized by 29–41% vegetation, 19–25% roofs and 29–39% paved surfaces, which demonstrates that over 60% of an urban surface can be covered by hard, man-made, heat-absorbent surfaces. This effect is starkly present in Baltimore, the largest city in Maryland. According to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) report, some areas in the city can be 10–15 degrees F hotter than other parts, at the same time on a given day [21].

The concentrated volume of machinery, heat emitting devices, and automobiles that are condensed in inner-city communities also contribute to the higher temperatures. To combat higher temperatures, there is often a need to run air conditioning units or electrical cooling devices more often and longer to provide relief, which cause more energy consumption and higher electrical usage — Maryland annually consumes 61.8 TWh (2% of the US total) of electricity as well as 7,800 MSTN of coal with 202 Bcf of natural gas, both of which are 1% of the US total respectively [22]. The higher energy demand in these locations causes additional heat problems for people that live in these areas due to the emissions of greenhouse gasses that create a feedback loop of increasing temperature into the future. Air pollutants such as ground level ozone may result from the higher use of machinery and air conditioning needed to stay cool which causes health problems for people that live in these inner-city environments. Ground level ozone can exacerbate respiratory conditions like asthma, inflame internal pathways, damage your throat and lungs, and more [23]. Also, there are other negative health effects stemming from ground level ozone which are currently being discovered. For example, one study indicated that higher levels of ozone exposure is associated with increased acute effects of sickle cell disease [24], a genetic disorder most commonly found in African American populations.

Caption: A graphic illustrating the formation of ground level ozone, which can cause serious adverse health effects. As indicated, substances from industrial pollutant sources, automobile exhaust, and sunlight can cause this toxic phenomenon. SOURCE: Washington State Department of Ecology

Additional Effects of the Heat on Maryland’s Population

Human beings have the ability to thermoregulate their own temperatures through autonomous processes in the body. Sweating, for example, is one way that the body will attempt to reduce its own body temperature by putting moisture onto the surface of the skin. Problems arise during high heat conditions when external temperatures are so high that the body is forced to begin to dehydrate in order to reach its demands for water. This issue was forced into the public eye in Maryland in 2018, when a University of Maryland football player died as a result of a heatstroke [25]. Also, people living in the hottest areas of the state, including the Eastern Chesapeake Shore have higher rates of chronic illnesses exacerbated by heat, including asthma and COPD and in some places. Furthermore, the rate of emergency medical calls can double when the heat index hits 103 degrees [26].

Caption: The thermoregulation process of a human body. SOURCE: Grodzinsky & Levander

For many residents the air quality issues that accompany higher heat conditions will worsen already tenuous health situations. Compared to 2010, increases in the frequency of extreme heat events during summer months in 2040 are projected to increase the rate of hospitalization for asthma in Maryland and the magnitude of the increase in asthma hospitalization rate is projected to be significant [27]. Children and elderly are especially vulnerable to compromised air quality due to existing air quality issues. In Maryland, the extreme heat related risk of hospitalization was most pronounced in the 5–17 year olds (36%) followed by 18–64 year olds (28%). Exposure to summertime extreme heat events increased the risk of hospitalization for asthma by 20% in Prince George’s County [27].

Rising extreme heat will also magnify health issues related to chronic conditions. For example, organ systems compromised from diseases such as diabetes face additional pressure in the summer months. And according to the Maryland Department of Health reported, by 2040, extreme heat events are projected to increase rates of asthma hospitalizations, Salmonella infections, rates of heart attacks, and a whole host of other problems, in Baltimore City and the state as a whole [13].

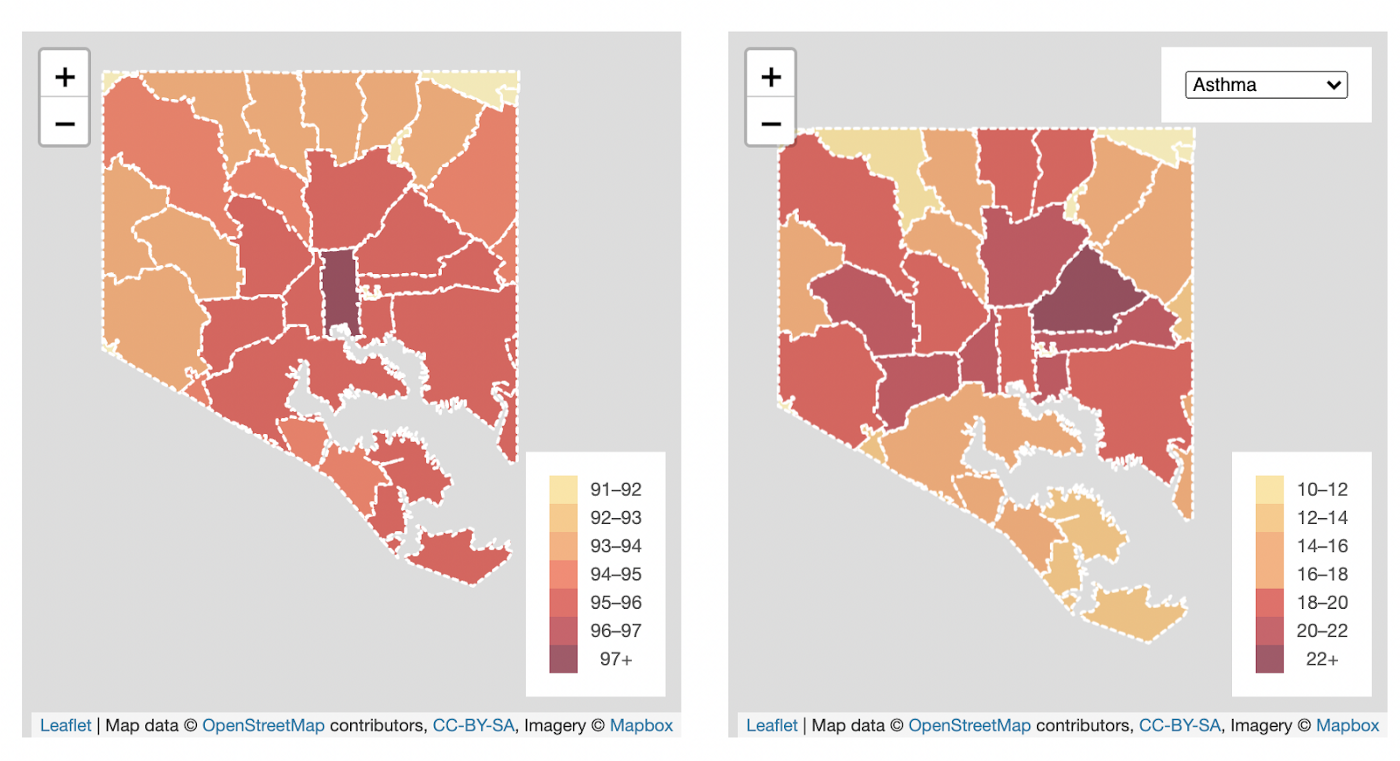

Caption: A comparison of median temperature measured on August 29, 2018 by zip code in Baltimore City, Maryland, (pictured left) and rates of asthma among hospital-admitted Medicaid patients from 2013–2018 in Baltimore City, MD. Generally, areas with higher temperatures also experienced higher levels of asthma. SOURCES: Urban heat island assessment of Baltimore on August 29, 2018 by researchers at Portland State University in Oregon and the Science Museum of Virginia. Hospital admissions data from the Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission. Data analysis by Roxanne Ready, Sean Mussenden and Jake Gluck.

Caption: The chart above quantifies heat-resulting deaths throughout various Maryland counties annually from 2014 to 2018. As can be seen, 2018 heat deaths in Baltimore and Prince Geroge’s County are far higher than those in other Maryland counties. SOURCE: 2018 Heat-related Illness Surveillance Report by the Maryland Department of Health

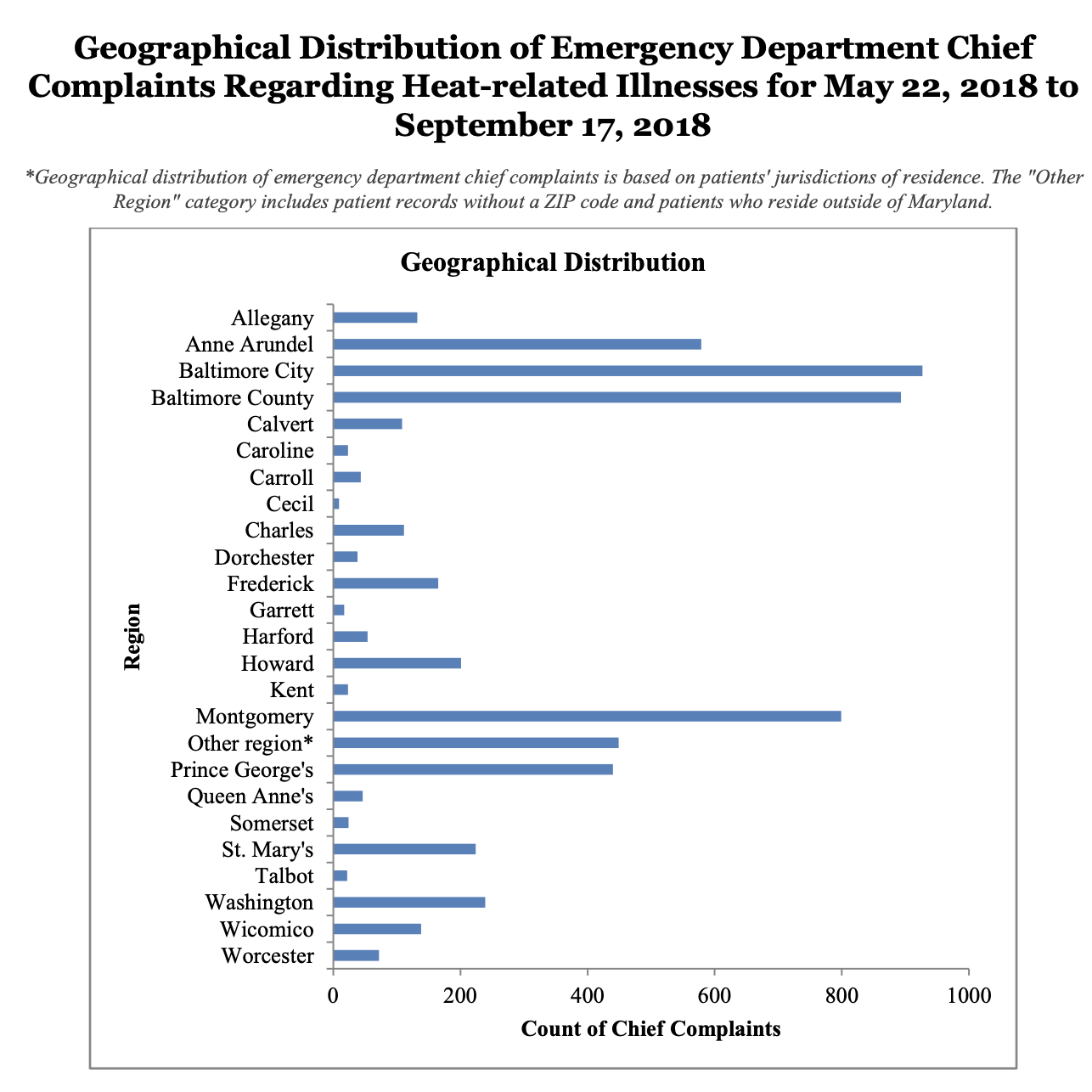

Caption: The graph above demonstrates heat-caused illness complaints within Maryland counties in the indicated 2018-sheltered time frame. As shown, within the time frame, Baltimore City, Baltimore County, and Montgomery County have significantly higher complaints, approximately 1,000, 900, and 800, respectively. SOURCE: 2018 Heat-related Illness Surveillance Report by the Maryland Department of Health

Heat Issues in Baltimore

Average annual temperatures in Baltimore have gone up more than 3 degrees over the last century, nearly twice as much as the rest of the country [27]. The architecture in Maryland in addition to the dearth of greenspace has contributed to heat disparities compared to the rest of the country. Researchers estimate the number of VERY HOT DAYS in Baltimore could increase six-fold by 2050. The city has already been significantly affected by these heat conditions. Between 2012 and 2018, there were 134 heat-related deaths in Maryland. Thirty-seven of those deaths (28%) occured in Baltimore, even though Baltimore accounts for a 10% of the state population [27]. Baltimore is already dealing with many health issues that a warming climate with more frequent and intense heat waves will only continue to jeopardize. The city has a predominantly African American community which makes up 64% of the total population, and the leading causes of death are heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, and HIV infection. [27]

Caption: A graphic showing the relative temperatures of neighborhoods in Baltimore City, Maryland. It highlights a specific example between Dickeyville/Franklin and Madison/Eastend, linking heat to other indicators and characteristics. SOURCES: Sources: Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance 2017 demographic data; Urban heat island assessment of Baltimore on August 29, 2018 by researchers at Portland State University in Oregon and the Science Museum of Virginia. Data analysis by Roxanne Ready, Sean Mussenden and Adam Marton.

The current conditions and strain that these events cause can be attributed to the history of housing, healthcare and food injustices that the African American population has had to endure for decades.

In 1910, Baltimore city enacted legislation that bolstered the racial segregation of neighborhoods. Housing developments and neighborhoods created restrictive enclaves that refused to admit Jews and African Americans. As a result, housing was clearly divided by racial delineation. Similar policies remained throughout the years, such as the city real estate board disallowing black agents until the 1960s, the many banks declining to provide loans to African Americans [27].

Caption: The redlined mortgage assessment maps created by the Homeowners Loan Corporation during the 1930s. SOURCE: The University of Richmond “Mapping Inequality” Project

During the 1930s, the federal Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) created a series of maps for many American cities including Baltimore, meant to advise lenders on which neighborhoods they should and should not lend to based on perceived lending risk. The maps follow a color-coded scheme of green, blue, yellow, and red, with each respective color indicating more undesirable lending conditions, starting with green being considered the most desirable and low-risk. Importantly, the green and blue areas also largely reflected wealthy and middle class white families, while the yellow and red areas contained poorer communities of color. Today, the divisions seen in this document persist, exemplifying modern day reverberations of redlining [27].

Caption: A new map of the city shows how its current poverty rates match up to racist mortgage policies of the past. SOURCE: Bloomberg article from April 30, 2015

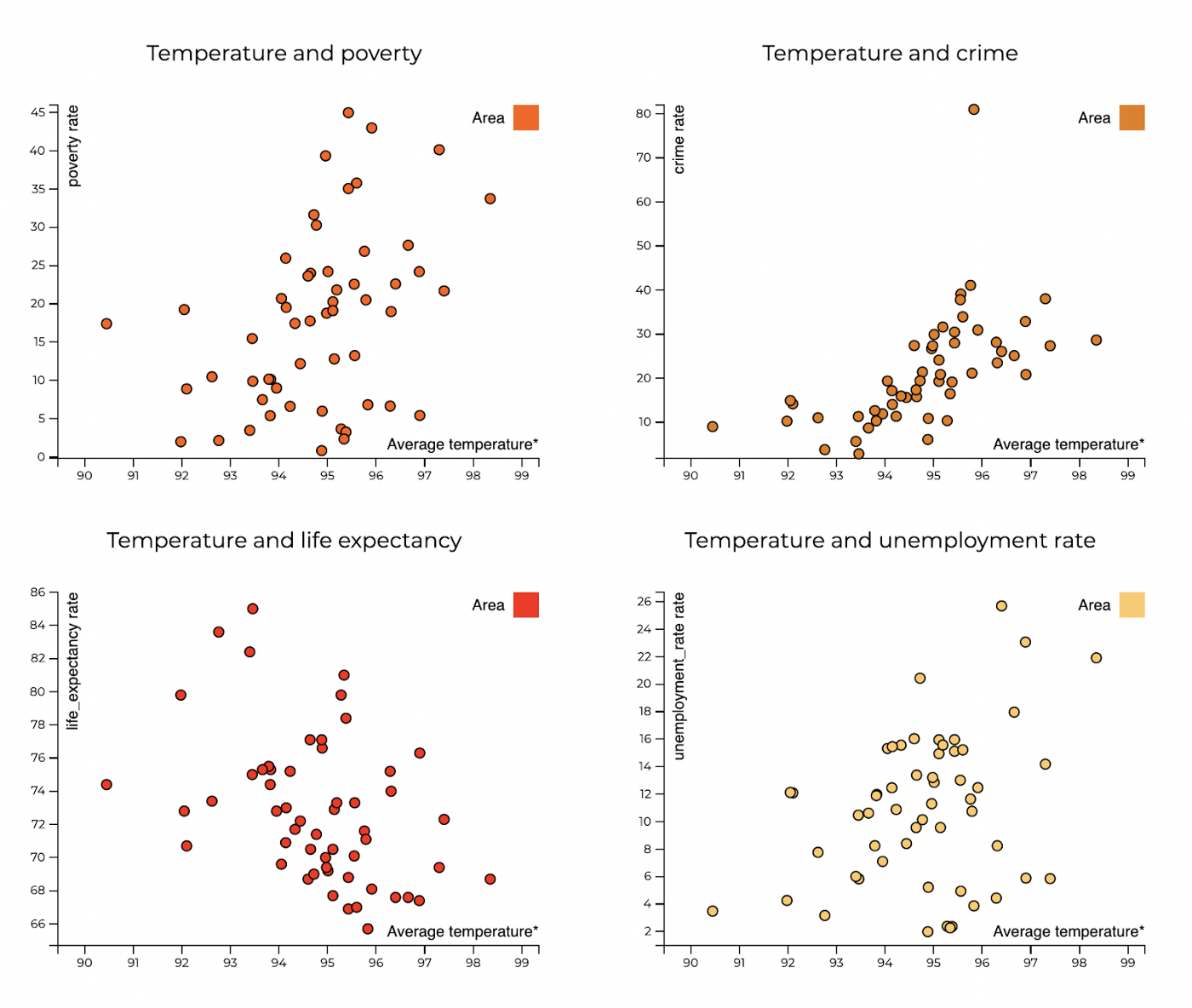

The impact of historic injustices on modern-day unequally distributed health consequences in cities such as Baltimore is clear. As we have established, communities that suffer the most from dangerous heat are the same ones that deal the most with other burdens including poverty, elevated crime and unemployment, and low life expectancy. Figures from the Howard University “Code Red” project illustrate this [27]. Further, the project shows that these vulnerable communities generally lack tree cover, which is an important tool to alleviate issues stemming from excess heat.

Caption: These graphics plot neighborhoods in Baltimore based on their average temperature and poverty rate, crime rate, life expectancy, and unemployment rate. They generally show that higher average temperatures are correlated with less desirable socioeconomic factors. SOURCES: Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance 2017 demographic data; Urban heat island assessment of Baltimore on August 29, 2018 (average afternoon temperature)* by researchers at Portland State University in Oregon and the Science Museum of Virginia. Data analysis by Howard University affiliates Roxanne Ready, Sean Mussenden and Adam Marton.

Caption: The graphic plots neighborhoods in Baltimore based on their percent of households living below the poverty line and percent of land covered by trees. Generally, communities with higher poverty rates have less tree cover. SOURCES: Howard Center for Investigative Journalism and Capital News Service analysis of 2015 tree canopy data via U.S. Forest Service and University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab; poverty data via U.S. Census Bureau.

“Redlining left Black families out of the mortgage market. It left them vulnerable to predatory lenders. Most of all, it propagated a cycle of inequality, which many poor, Black Baltimore residents still find themselves in today.”

Redlining and a Warming Climate

Within Maryland, Baltimore demonstrates how consequences of heat can be segregated even on a granular scale, and amplify existing inequities. As we mentioned, neighborhoods in the City can experience heat at varying magnitudes, with the difference between the hottest and coldest neighborhoods being as high as a startling 10–15 degrees Fahrenheit [28]. Furthermore, the hot areas disproportionately tend to be poorer and include higher percentages of Black and Brown people than the colder areas. Simply put, in Baltimore (and countless other American cities), if you are not White or live in a low-income neighborhood, you will likely suffer more from the negative effects of excess heat, than those who live in wealthy or predominantly White neighborhoods. People in these poorer neighborhoods which experience extreme heat also are also more likely to live shorter lives, and face higher rates of violent crime and unemployment [27].

The aforementioned mortgage map created by the federal Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) during the 1930s mirrors the heat-related inequities in Baltimore today. According to the New York Times, in Baltimore, areas which received “A” and “B” ratings face lower temperatures in the summer compared to the city average. The “C” and “D” areas however, are 1.3 and 5.7 degrees F hotter than the city average, respectively [29]. This means that the areas which were deemed unsuitable for providing mortgages nearly 100 years ago, are now the ones suffering most from heat and related issues. It turns out that the discrimination present back then is still rooted in the city and thus the state as a whole, today.

Solutions to Heat Issues in the State of Maryland

When developing legislation or regulations that affect public health, policymakers and other stakeholders such as state agencies should inform their work by investigating potential negative climate effects, and preventative measures to protect against those effects. New policies should consider the cumulative impact that these processes would have on public health and vulnerable populations. In addition, those highly vulnerable communities should be prioritized when remedying effects of heat exposure. Throughout Maryland, there are various solutions being proposed and implemented to counter excessive heat exposure, resulting issues, and other climate change topics:

2030 Maryland Greenhouse Gas Reduction Plan — A 279 page document from the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) that outlines Maryland’s plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and associated negative impacts. The plan discusses programs across a diverse array of industries and sectors, from transportation to electricity generation to forest management, and everything in between. It estimates that these programs will create an additional 6,800 jobs and a $14.7 billion GDP boost for the state. The plan is comprehensive and rightfully addresses environmental justice for vulnerable communities through programs such as funding for community solar systems, large investments in clean energy for low-income households, tree planting and increasing park spaces in underserved areas, clean-energy public transportation, and more. However, concern lingers because the document is not an actual piece of legislation. As Kim Cobe, the executive director of the Maryland League of Conservation Voters (MLCV) said, “they have put out something ambitious, but how do we know it is going to be implemented?” [30] [31]

Maryland House Bill 722 — Adopted in 2020, this law requires the state’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration to create regulations that will require employers to protect employees from heat-related illnesses. The American Industrial Hygiene Association supported the passage of the bill, and the president of the association said, “Heat stress is a significant problem that can result in occupational illnesses and injuries, and in some cases death. This bill is both timely and needed.” While the intent of the law is relevant for protecting against negative effects of excess heat, the specific legislation to be enacted remains to be created. These regulations should include potent compliance enforcement methods, and ensure equitable enforcement across industries; for example, a field like construction which in many cases employs low-income migrant workers and has a history of worker exploitation, should be especially scrutinized. [32]

Prince George’s County 2025 Environmental Justice Plan — The plan — prepared by CEEJH- discusses environmental issues and presents strategies to combat them for Prince George’s County, which are also relevant to the rest of the state. Topics include lead, water quality, food security, cumulative impacts of environmental hazards, and equitable development, zoning, and planning. It is thorough in addressing equity and justice for vulnerable communities and can be used as a model for future action. Principles from this plan can be applied to reduce proliferation of urban heat islands and the health consequences they bring.

Schoolyard Urban Heat Studies — A program run by the Hood College Center for Coastal and Watershed Studies that aims to teach educators about urban heat, potential impacts of schoolyards acting as urban heat islands, and ways to do related activities with students. [33]

Baltimore’s Growing Home Campaign — Since 2006, Baltimore County’s Growing Home Campaign has provided $10 coupons to homeowners toward the purchase of most trees at local nurseries. Each coupon represents $5 of public funds and $5 of retail funds. In order to validate their coupon, homeowners provide information including tree type and location planted, allowing the county to integrate the data with future tree canopy studies. The county began the program as an innovative way to increase tree canopy cover as part of its larger “Green Renaissance” forest conservation and sustainability plan. In the first two months of the program, 1,700 trees were planted. [34]

Baltimore Climate Action Plan — The action plan promotes cooling and green roof technology, with the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by nearly 7,000 metric tons, and achieving a 30% participation rate from commercial buildings and residential buildings, respectively, by 2020 [34]. It discusses programs that will support goals related to equity and environmental justice, such as promoting pedestrian access and increasing greenspace. However, the plan calls for physical infrastructure development, which has been used in the past to uproot vulnerable populations and create reverberating negative impacts like highway development leading to urban heat islands. Thus, as the document itself notes, it is essential to engage community stakeholders in the planning, development, and execution phases of implementation, to prevent these injustices from being repeated.

Baltimore Cooling Centers — There are 7 senior centers in Baltimore that serve as cooling centers Monday through Friday. These are meant to be spaces where people can cool off during intolerable and unhealthy heat. Currently, only 1 community cooling center is open 7 days a week as listed on the Baltimore City Health Department website [34].

Important and Relevant Bills

Blueprint for Maryland’s Future (HB1300) — In 2016, the Maryland legislature created the “Kirwan Commission,” tasked with developing recommendations for preparing Maryland students for the modern world. This bill stemmed from proposals from the commission. It laid out a 10-year plan to expand pre-kindergarten options, increase funding and resources such as tutors for high schools in impoverished areas, establish new pay and career opportunities for teachers, and create an accountability board for the implementation of these programs. The accountability board component solidified the bills strength and potential positive impact, as it helps prevent the funds being allocated from being wrongfully or irresponsibly spent. The bill was originally vetoed by Governor Larry Hogan, but the veto was overridden and the bill became law in February 2021. As outlined below, there were proposals to fund the plan using climate-related solutions. [35]

Climate Crisis and Education Act (MD HB33) — This bill would place fees on companies responsible for emitting carbon, phase in fees on high-pollution vehicles, require the state to reduce carbon emissions 60% relative to 2006 by 2030, and achieve net zero emissions by 2045. It is projected to produce $1.4 billion in revenue by 2026, which would be invested into education, green infrastructure, and protections for low-income families, by funding the “Blueprint for Maryland’s Future” act. It would also create a state Climate Crisis Council to develop plans to curtail greenhouse gas emissions. The bill would be a positive step to assist underserved communities, because the funds collected from polluting entities would be directed to programs like stormwater management and emergency room costs, which are typically picked up by taxpayers and can be difficult to obtain for low-income individuals. On March 1st, 2021, the bill was voted down in committee and remains in that state. [36]

Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard and Geothermal Heating and Cooling Systems (HB1007) — Aiming to promote geothermal energy, the bill requires that by 2028, 1% of Maryland’s Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard (RPS) come from in-state geothermal energy. The RPS program mandates that electricity suppliers use certain portions of various renewable energy sources for their retail electricity sales. The bill would greatly increase the role of geothermal energy in Maryland, encourage geothermal energy infrastructure in the state, and reduce carbon emissions by 140,000 tons yearly. Importantly, like all other legislation which promotes physical infrastructure development, it will be important to engage community stakeholders throughout the implementation process to prevent vulnerable populations from being displaced. The bill was signed into law in 2021. [37]

Maryland Clean Energy Jobs Act (SB 516) — Passed by a large majority in both branches of the state legislature in 2019, this act is “the clean-energy legislation ever passed in Maryland in the fight against climate change” [38]. It sets requirements to transition 50% of the state’s electricity to renewable sources as defined by the aforementioned RPS program by 2030, and 100% by 2040. Additionally, it will create 20,000 new jobs supported by clean energy, bolster career programs for communities of color, and heavily cut carbon emissions. Unfortunately, the most significant shortcoming of the law is that it allows trash incinerators to remain as a “Tier 1” renewable energy source in the state RPS, meaning that even after the transition to renewables, some energy will come from trash incineration. This is a problem, because trash incinerators such as the BRESCO plant in Baltimore release harmful and dangerous pollutants into the air. Since the passage of the bill, various state policymakers such as Sen. Michael Hough (R-Frederick) have tried to remove this official state classification, but these efforts have thus far been to no avail [39]. [40]

Climate Solutions Now Act (SB0414 / HB 0583) — This expansive bill created various policies to take strong action against climate change consequences and sources. However, in April 2021, lawmakers failed to reconcile differing versions from the House and Senate, rendering it dead for now. For example, the state is currently mandated to reduce greenhouse gas emissions relative to 2006, by 40%; the House version aimed to bring that to 50%, while the Senate version proposed 60%. Additionally, the bill included provisions for green construction, solar panels for public schools, solar land use, and more. It still has room to grow by provisioning more resources to address environmental justice issues for underserved communities. Specifically, it would be strengthened if it marshals the creation of natural green infrastructure, such as open park space, gardens, rain barrels, soil beds, or permeable pavement. These would absorb stormwater runoff, support air quality, and help build a healthier community overall. The bill is also largely market-based and relies on fiscal policy, which should be amended by focusing more on direct action. Ultimately, although the whole bill was not advanced, portions of it such as the planting of 5 million new trees, made it into other bills that were signed into law. [41]

References

McDonald, R. M. (2019, May 8). Trees in the US annually prevent 1,200 deaths during heat waves. Cool Green Science. https://blog.nature.org/science/2019/05/08/trees-in-the-us-annually-prevent-1200-deaths-during-heat-waves/

Vaidyanathan, A. V., Malilay, J. M., Schramm, P. S., & Saha, S. S. (2020, June). Heat-Related Deaths — United States, 2004–2018. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6924a1.htm

Staff. (2021, January 22). The impact of climate change on maryland. The Southern Maryland Chronicle. https://southernmarylandchronicle.com/2021/01/22/the-impact-of-climate-change-on-maryland/

Maryland Department of Health. (2019, October). 2019 heat-related illness surveillance summary report. https://health.maryland.gov/preparedness/Documents/2019%20Summary%20Heat%20Report.pdf

Maryland’s sea level is rising. (2021). Sea Level Rise. https://sealevelrise.org/states/maryland/

Rising sea level. (2021). Maryland Sea Grant. https://www.mdsg.umd.edu/topics/coastal-flooding/rising-sea-level

Climate change program. (2021). Maryland Department of the Environment. https://mde.maryland.gov/programs/Air/ClimateChange/Pages/index.aspx

Poon, L. P. (2019, May 24). In a town shaped by water, the river is winning. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/tosv2.html?vid=&uuid=a2aea850-efb0-11eb-9ad4-252db86ba6fc__a2aea850-efb0-11eb-9ad4-252db86ba6fc&url=L25ld3MvYXJ0aWNsZXMvMjAxOS0wNS0yNC9hLWhpc3RvcmljLXJpdmVyLXRvd24tY29uZnJvbnRzLWEtZmxvb2RlZC1mdXR1cmU=

Climate change. (2021). Chesapeake Bay Program. https://www.chesapeakebay.net/issues/climate_change

Major cities with the biggest projected temperature changes by 2050. (2021, July 1). Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/weather/weather-news/sns-stacker-major-cities-temperature-change-20210701-q3vhom6e6fd6bpppwfsecyqanm-photogallery.html

Baltimore, Maryland population 2021 (demographics, maps, graphs). (2021). World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/baltimore-md-population

Northern Hemisphere just had its hottest summer on record. (2020, September 14). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.noaa.gov/news/northern-hemisphere-just-had-its-hottest-summer-on-record

Maryland Institute for Applied Environmental Health & University of Maryland School of Public Health College Park. (2016, April). Maryland climate and health profile report. https://mde.maryland.gov/programs/Marylander/Documents/MCCC/Publications/Reports/MarylandClimateandHealthProfileReport.pdf

City of Rockville. (2020). Climate hazards and risks. https://www.rockvillemd.gov/DocumentCenter/View/39312/Climate-Hazards-and-Risks?bidId=

University of Massachusetts Amherst. (2021). Climate change state profiles Maryland [Slides]. University of Massachusetts Amherst. https://www.geo.umass.edu/climate/stateClimateReports/MD_ClimateReport_CSRC.pdf

World Meteorological Organization. 1984. “Urban Climatology and its Applications with Special Regard to Tropical Areas.” Proceedings of the Technical Conference Organized by the World Meteorological Organization, Mexico, 26–30 November 1984 (WMO-№652): 534.

Oke T.R., 1987. Boundary Layer Climates, Second Edition., London: Methuen and Co., 435.

Gorsevski, V, Taha, H, Quattrochi, D, & Luvall, J. Air pollution prevention through urban heat island mitigation: An update on the urban heat island pilot project. United States.

Jeromin, K. J. (2021, July 15). These cities have the most stifling heat islands in the United States. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2021/07/15/heat-island-rankings-climate-central/

Akbari, H., & Rose, L. S. (2008). Urban surfaces and heat island mitigation potentials. Journal of the Human-Environment System, 11(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1618/jhes.11.85

Dance, S. D. (2018). Some Baltimore blocks could be 15 degrees hotter than others. Mapping them could help address heat hazards. The Baltimore Sun. https://www.baltimoresun.com/weather/bs-md-heat-island-research-20180827-story.html

United States Department of Energy. (2021). State of Maryland energy sector risk profile. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2016/09/f33/MD_Energy%20Sector%20Risk%20Profile.pdf

Health effects of ozone pollution. (2021, May 5). US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/ground-level-ozone-pollution/health-effects-ozone-pollution

Tewari, S., Brousse, V., Piel, F. B., Menzel, S., & Rees, D. C. (2015). Environmental determinants of severity in sickle cell disease. Haematologica, 100(9), 1108–1116. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2014.120030

Allen, K. A. (2018, August 13). Heatstroke dangers reinforced by investigation into death of college football player. USA Today. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/sports/ncaaf/2018/08/12/heatstroke-maryland-death-practice-korey-stringer-jordan-mcnair/967134002/

Capital News Service. (2019, September 7). Health risks rise with the temperature. Baltimore Fishbowl. https://baltimorefishbowl.com/stories/health-risks-rise-with-the-temperature/

Round, I. R., Conner, J. C., Rowley, J. R., & Banisky, S. B. (2019, September 3). Heat & inequity. Capital News Service. https://cnsmaryland.org/interactives/summer-2019/code-red/neighborhood-heat-inequality.html

Anderson, M. G., & Mcminn, S. M. (2019, September 3). As rising heat bakes U.S cities, the poor often feel it most. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2019/09/03/754044732/as-rising-heat-bakes-u-s-cities-the-poor-often-feel-it-most

Plumer, B., Popovich, N., & Palmer, B. (2021, April 20). How decades of racist housing policy left neighborhoods sweltering. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/08/24/climate/racism-redlining-cities-global-warming.html

Shwe, E. (2021, May 8). Department of the Environment releases a climate action plan — 14 months after deadline. Maryland Matters. https://www.marylandmatters.org/2021/02/20/14-months-late-maryland-department-of-the-environment-releases-a-climate-action-plan/

Maryland Department of the Environment. (2021, February). The greenhouse gas emissions reduction act. https://mde.maryland.gov/programs/Air/ClimateChange/Documents/2030%20GGRA%20Plan/THE%202030%20GGRA%20PLAN.pdf

Maryland enacts AIHA-support bill protecting workers from heat stress. (2020, May 18). Occupational Health & Safety. https://ohsonline.com/articles/2020/05/18/maryland-enacts-aihasupport-bill-protecting-workers-from-heat-stress.aspx

Schoolyard Urban Heat Studies. (2021, July 27). Hood College. https://www.hood.edu/academics/departments/department-biology/center-coastal-watershed-studies/education/schoolyard-urban-heat-studies#:%7E:text=Hood%2DCCWS’s%20Schoolyard%20Urban%20Heat,caused%20by%20development%20%26%20impervious%20surfaces.

Programs. (2021). Department of Recreation & Parks. https://bcrp.baltimorecity.gov/forestry/treebaltimore/programs

Shwe, E., & Gaines, D. G. (2021, February 12). With override sotes, senate passes landmark education reform and digital ad tax bills into law. Maryland Matters. https://www.marylandmatters.org/2021/02/12/with-override-votes-senate-passes-landmark-education-reform-and-digital-ad-tax-bills-into-law/

Shwe, E. (2021b, May 16). Lawmakers consider carbon fees for polluters that will help pay for Kirwan bill. Maryland Matters. https://www.marylandmatters.org/2021/02/19/lawmakers-consider-carbon-fees-for-polluters-that-will-help-pay-for-kirwan-bill/

Shwe, E. (2021c, May 18). Maryland eyes expansion of geothermal industry. Maryland Matters. https://www.marylandmatters.org/2021/05/18/maryland-eyes-expansion-of-geothermal-industry/

CCAN. (2019, April 15). The Maryland Clean Energy Jobs Act: A great bill with unfinished business on waste incineration. Chesapeake Climate Action Network. https://chesapeakeclimate.org/the-maryland-clean-energy-jobs-act-a-great-bill-with-unfinished-business-on-waste-incineration/

Kurtz, J. (2021, February 11). Hough tries new approach in bid to end clean energy subsidies for trash incinerators. Maryland Matters. https://www.marylandmatters.org/2021/02/11/hough-tries-new-approach-in-bid-to-end-clean-energy-subsidies-for-trash-incinerators/

Reflecting on the MD Clean Energy Jobs Act. (2019, April 15). Sierra Club. https://www.sierraclub.org/maryland/blog/2019/04/reflecting-md-clean-energy-jobs-act

Shwe, E. (2021a, April 21). Climate bill dies as House and Senate Fail to compromise. Maryland Matters. https://www.marylandmatters.org/2021/04/13/climate-bill-dies-as-house-and-senate-fail-to-compromise/

Link to this post on our Medium page: https://ceejh.medium.com/heatwave-hell-in-maryland-fa33e7153c0a